Biography

Parish Priest Carlo Manché – "A Great Christian"

By Mons. Prof. Arturo Bonnici, DD, BA, BL Can, HEL

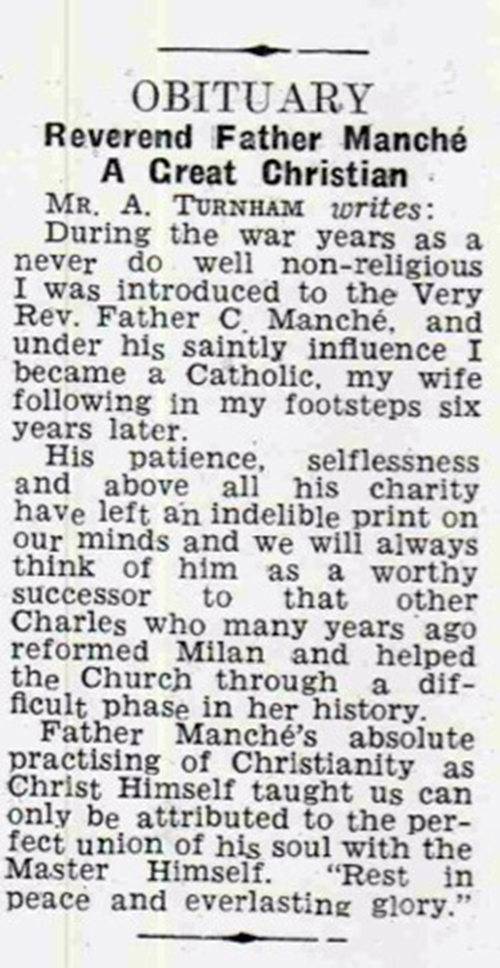

Under the above heading an ex-Protestant Englishman, a certain Mr A Turnham, published an appreciation in the Times of Malta, upon the death of the Parish Priest of Gżira, Fr Carlo Manché, who had converted him to Catholicism.

“His tolerance, his altruism and, above all, his charity left an indelible mark engraved within us, and we always remember him as a worthy successor of the other Carlo (Borromeo), who a long time ago, reformed Milan and helped the Church in a difficult phase in its history. His absolute practice of Christian life, just as Christ himself taught us, was the product of his perfect union with the Lord.”

Was this statement correct? This is what we shall see in this biography published by the Society of Priests Christus Rex twenty-five years after the death of the much-loved Fr Carlo Manché.

Who and what was this “great Christian”?

Fr Carlo is born

Fr Carlo was born in Valletta, Malta on the 22nd of September 1905 and was baptised in the Church of Porto Salvo. He was one of seven children, whom the Doctor Surgeon Charles Manché, Lieutenant-Colonel in the English Army, had with his first wife, Josephine neé Falzon, and a brother to eight other siblings whom the same doctor had with his second wife, Lucrezia neé Tanti.

Of the family Manché the first one I knew was the grandfather of Fr Carlo, Prof Lorenzo Manché, a well-known ophthalmologist before Prof Luigi Preziosi began his career. I recall, when I was about 9 years old, I was taken to his place in Alexander Street, Valletta. They took me up the stairs on the side of Kingsgate to his clinic. He checked my eyes and prescribed spectacles. Prof Lorenzo Manché was a well-known scientist, a patriot and above all a fervent and most charitable Christian.

Fr Carlo as a child

More than once, continued Prof Manché, he ran away from home. He used to go to Mortimer’s shop and then return home pushing a pram with a baby in it, whom the English women used to leave in the shop’s entrance, until she went upstairs to buy something. Needless to say, his parents used to send him back with the pram and the baby. But in the meantime, poor mothers, just imagine how miserable they would become, not knowing what had happened to their children. Do you think it could have been the desire in him to protect the children who, he may have thought, had been abandoned?

His Education

Fr Carlo received his first religious and civil education at home from his parents. Everyone knows the Manché family as very good religiously and very cultured intellectually. Socially everyone knew them as charitable. Who knows how many patients with eye diseases Prof Lorenzo and his son Doctor Charles Manché treated free of charge at their clinic!

Fr Carlo was raised under the discipline of a father used to English Military Service and turned out disciplined. His brother told me that, when they were young, their parents used to dress them as sailors. It was the fashion in those days because even I had a sailor’s outfit. Once, when King Edward VII visited Malta, the Manché brothers, dressed as sailors, went near the cannon at the Upper Barrakka to wait for the King to pass by for the religious service in the church that used to be where today there is the Parcel Post Office. As they saw the King approaching, they stood in line and saluted him. The King drew closer to talk to them. He found Maltese children, who could speak perfect English, as that was the language they spoke at home.

When he dressed as a sailor, Carlo used to feel superior, as if he was really a sailor during service. Prof Manché told me that, when his brother wore that dress on Sundays, he did not want to play as usual with the boy next door nicknamed “il-Paqqa”. The boy used to feel offended. But the next day they would again talk and play with each other … as during the week Carlo would not be in service!

As long as they continued to live in Valletta, Carlo frequented the Maltese Institute of Catholic Education (St Jacob) and, as during his childhood Carlo did not speak well in Maltese, Mons. Enrico Dandria taught him Catechism in English.

At the Christian Brothers and the Lyceum

The first primary school that Carlo frequented was Stella Maris College run by the Christian Brothers in Villa Schinas, in Rudolph Street, Sliema, as in the meantime, the Manché family had moved from Valletta to Gżira.

It is a pity that none of the teachers who taught Carlo at that school is still alive, as we would have found out more about him. I found out from his brother that Carlo used to enjoy serving the priest saying mass at the school. Those religious have good reason to be so pleased that their school produced a student, who does them proud for his wisdom and his saintliness.

From the Christian Brothers he moved on to the Lyceum where he continued his studies, until in 1921, he passed the Matriculation exam. I had passed that exam a year before him, but, as the university course started every three years, I had to wait one year and so Fr Carlo and I started the Literature course, or the Theology Preparatory course.

University Student

I do not know why Fr Carlo did not start the academic course for the Literature degree, although he was a very intelligent young man and he had a good grasp of the English language, with an enormous predisposition to all foreign languages. For that reason he was not noticed much in that course. However, as soon as he started the Theology course, everything changed. It became apparent that in that course he found the subjects to his liking – Theology, Scripture and Canon Law. And for me, who always used to come first in the Preparatory course, he changed everything because during the four years he did not give me any opportunity to beat him in marks. He used to come first and, as there were only two of us, I used to come last.

We both used to study. We competed to get the highest marks; but, believe me, between us there was never any rivalry or envy. On the contrary, at the Seminary we really got on well together.

We wore the cassock together

I mentioned the Seminary because in October 1924 we entered the seminary in preparation for the priesthood. Our superiors were Mons Archdeacon Joseph Apap Bologna as Rector, Mons Joseph Darmanin as Vice-Rector, and Canon Theologian (later Titular Bishop of Tralles and Auxiliary Bishop of Malta) Emmanuel Galea as Prefect of Studies.

In their wisdom they chose the 4th of November, the feast of St Charles, as the day on which we should wear the cassock for the first time. I could not be offended, as my saint does not appear on the Roman calendar.

How happy we were with the service! In my case, as I had never been an altar boy, and in his case, as at the Christian Brothers he used to wear only the “żimarra” (a long gown). The next day, I recall, we went to university and our professors were so happy for us. Good Mons Karmenu Zammit told us: “Look after it!” On the day I wore it for the first time, I got stuck to the railings of the stairs and tore it, then promptly replied: “I’ve already torn it.” “No, my son, I mean it in another sense: Look after it.” Then I understood the spiritual sense of the words of that saintly professor. Did the Parish Priest Manché ever tear his cassock? Is there anyone who can say: “Yes”?

At the Seminary I got to know Manché well. He was a good man, studious and precise. And this was confirmed by everyone, who had anything to do with him and gave us some information about him.

Manché the musician

The Manché family is well known as a family of musicians: everyone is able to play an instrument or more. When he came to the Seminary, Fr Carlo brought with him a violin, which he could play well, and a guitar, which he played better (he could also play the oboe). After our first year at the Seminary, Fr Cesarin Attard, who used to play the harmonium in the chapel, became a priest and left. Who was going to take his place? There was no musician other than Manché! But he could play neither the piano nor the harmonium. So he brought a small concertina – I can still see it in his hand – and he used to lead the singing on it. Then, he started staying in at the time of our walk to take piano lessons with Maestro Diacono and before long he started to play and lead us on the harmonium.

In those days, Fr Karlu, an Augustinian, used to come every Sunday to the Seminary to teach us singing. When a feast was approaching, in which Archbishop Caruana would wish us Seminarians to sing Gregorian Chant, he would come to teach us and he would ask Fr Carlo to strengthen us further during the interval. I can still remember him with the pitch-pipe between his fingers, placing it in his mouth to get the note and, with one hand raised, he used to lead us. On our part there was always some joke and he used to smile. In the meantime singing at St. John’s ceased and Manché used to prepare us to sing some Gregorian Mass.

For some time Fr Carlo was our prefect. He had a defect. As soon as he woke up in the morning or in the afternoon, he left his cell more asleep than awake and we used to push him around to wake him up. He seemed to enjoy it and he let us push him. This defect, Mr Ġanni Cauchi told us, he kept even when he became Parish Priest. However, he went on, when he was called for assistance during the night, he lost all his sleepiness, so strong was his will to do his duty well.

A man of precision

Manché’s cell at the Seminary was similar to a doll’s house. Everything in its place and clean, the bed neatly made and a desk with the books all in order. Let me relate to you what happened one day. It was a Sunday. Before we left to go to St John’s, I felt like making a practical joke on him. When he came out from his cell, I went in and messed it up. Books thrown here and there, his candle knocked over, his chair upside down, but I did not touch his bed. That morning while we were still at St John’s, some Prelate from overseas arrived and was shown around the Seminary. The Rector, who knew how tidy Manché usually kept his room better than ours, to give him a sense of the tidiness that existed at the Seminary, decided to take him into Manché’s room. You can just imagine how surprised and mortified the Rector was, when he found all that mess! When we returned, the Rector called him and told him about the mess that he found in his room.” I don’t know, “replied Manché,” I left the room as I normally do.” When he told us about this matter, I confessed my sin and asked for his forgiveness. But with Manché there was no need to apologise, even if you do him harm intentionally – much less if one innocently jokes with him and the joke causes harm.

Fr Carlo was not a scrupulous person, but he had a very sensitive conscience. I remember that for some time, when he used to study about sexual matters, he used to wear the surplice to keep his soul raised towards Heaven, even when thinking about earthly matters. I seem to think that he had told us that that is what he had read that St Alphonse de Liguori or some other saint used to do.

At the Seminary the seminarians were not allowed to smoke more than three cigarettes a day, one after coffee, one after lunch and one after dinner. Fr Carlo used to enjoy smoking cigarettes and he used to feel the urge to smoke during the time of study, but he also used to feel obliged to obey the rule. In this struggle he managed to find a compromise that was approved by the Superiors, not so much because it stopped any abuses, but because it was suggested by Manché. He suggested that the three cigarettes permitted daily be split into six halves and that three halves are smoked during the prescribed times and the other three during study.

Priestly Ordination

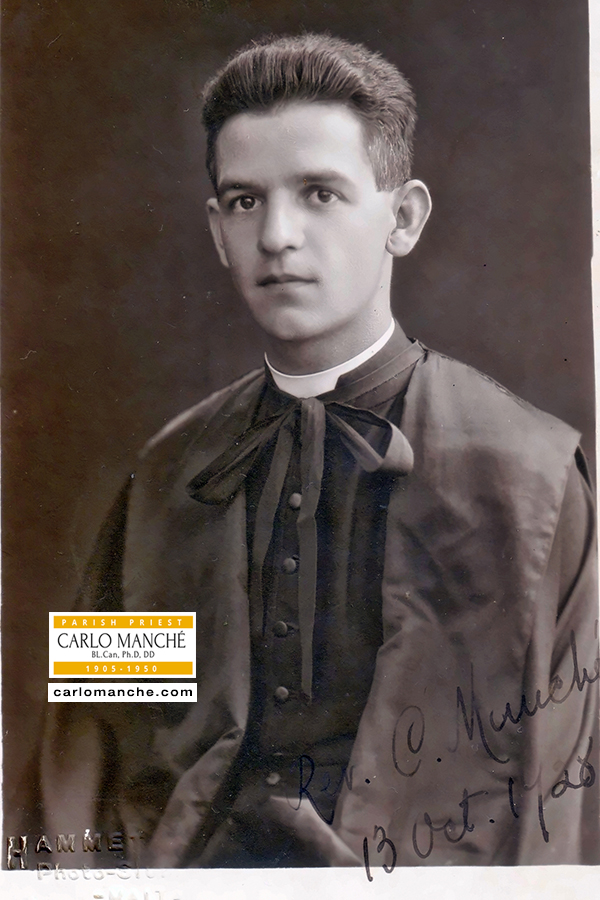

After the first year Theology examination we started the process of ordination. On 18 September 1925 we received the tonsure at the Seminary and the following day the Ostiary and the Lectorate. On the 18th of the same month of the following year we were granted the minor ordination of Exorcist and Acolyte. On 24 September 1927 we were ordained Subdeacons, or we became committed, as we used to say. On 24 March 1928 we became Deacons. On 22 September of the same year we were ordained priests. Archbishop Mawru Caruana conducted our ordinations at the Cathedral [in Mdina], except for the Deaconship which took place at St. John’s [in Valletta]. Fr Carlo said his first high mass in the church so-called “Tal-Ġebla” (“Of the Stone”), that is the Parish Church of Gżira. This took place without too much pomp on 23 September.

On 1 October we were conferred the degree in Theology and Bachelor of Canon Law. Fr Carlo came first in the course and won a scholarship to study at a university overseas. He chose to go to Rome, where he studied for two years in the Gregorian University and was conferred the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.

Fr Carlo – the Linguist

Fr Carlo had an excellent grasp of the English language, spoke Italian fluently and he wrote well in Latin. He could also speak French, Spanish and German.

One day an aunt of his came from Germany and Fr Carlo, still a Seminarian, wanted to speak to her in German. He started learning the language and to practice it with her and in no time he learned that language perfectly. I hear you say: how do you know that? I know because when I was still assistant secretary to the Archbishop, one day a young lady from Austria or Germany visited the office requesting me to apply for a marriage dispensation on her behalf, as her fiancé was a Protestant. To me she did not speak in German because I only know “Ja” and “Nicht” but to Fr Carlo, who was her Parish Priest, she used to speak in German. During our conversations she told me that his spoken German was perfect: in her own words, “He speaks German like a German.”

By the way, I forgot to tell you that he knew Hebrew quite well too. We studied Hebrew and Holy Scripture at university. I can still see the letters of the Hebrew alphabet that he wrote; they were beautiful and exact like those printed in the Jewish books. He had steady hands for calligraphy. This was certainly the product of the Frères’ school. (It is obvious that I never attended that school).

The beginning of his priestly life

A spiritually and intellectually well-formed priest is not one worth losing from service in a Diocese. Accordingly, when Fr Carlo returned from Rome, Archbishop Caruana appointed him Vice Parish Priest of Gżira and at the same time entrusted him with the duties of Prefect of Studies at the Archbishop’s Seminary. Fr Carlo served both positions with loyalty; but he still was not feeling comfortable. God had called him to a greater pastoral life.

With the death of the Parish Priest of Gzira, Fr Anton Manché, a third cousin of Carlo, Archbishop Caruana appointed Fr Carlo Parish Priest of that parish, which had increased in importance. On 12 March 1935, the new Parish Priest took possession of the parish, among the joy of the people who had already known him for his goodness, his work and his wisdom.

If, as we saw, Fr Carlo excelled in his studies and at music, we now see him glowing in his pastoral career. Fr Michael Angelo Camilleri gave me a pile of papers with sincere and reliable declarations made by persons who knew the new Parish Priest very well, lived and worked with him in the parish. From these declarations I extracted the following about the virtues, work and sacrifices of Fr Carlo Manché.

The Good Shepherd

His first piece of work in his parish as Parish Priest was to organise the clergy of the parish. To make the other priests feel as one family and that he was one of them, he changed the Parish House into a presbytery. There, the work of the parish could be studied, planned and carried out in a spirit of brotherhood and cooperation.

In second place, Fr Carlo wanted to complete the construction of the church for which he had collected money since he was a cleric, to furnish it and make it more beautiful, as is worthy of a Temple of God. He was a moderately progressive priest (not anti-traditional). He was one of the first to introduce benches instead of chairs, to have more order; he did not want too many altars, so that the major altar remains the centre of devotion; he had large and closed confessionals made for the freedom and comfort of the penitent; he ensured that during sacred functions the singing and music heard in church attracted one to God.

An Exceptional Confessor and Orator

Almost all the persons we mentioned stated that Fr Carlo considered the confessional as the place where he could do the most good, and said that he enjoyed hearing confessions for long periods, both in the morning and in the evening. Full of patience and with sweet and heavenly words he used to warn the penitent and prepare him for forgiveness. He also used to talk to some penitent about religious or priestly vocation. Sr Clotilde Schiavone, an Augustinian nun, told us that he was her confessor and that during confession he was able to inflame God’s love in you with his words.

There was a story about how once, at 11 o’clock at night, a man came knocking on his door for confession. The Parish Priest opened the door, asked him in and heard his confession. It must have been a huge consolation for him not to have sent him away, because the next day he heard that the penitent had died.

Another tool at his disposition in pastoral work was preaching. Parish Priest Manché used to prepare for it beforehand by reading spiritual books and by meditation. Thus, to all those who would congratulate him after a sermon, he would reply: “Congratulate the authors whom I’ve read!”

Every Sunday he used to give two Catechism lessons: one for children at 3.00 pm and the other at a time that he believed was more appropriate for adults. Some witnesses told us that, while his sermons were somewhat long, the church used to be full and no one would get fed up, so sweet and persuasive were his words. So much so, we were told that people from other parishes used to come to listen to his sermons.

On occasion he was invited to deliver spiritual exercises for the clergy, for lay people and for students. Sometimes the Archbishop himself attended. Both the priests and the lay people used to speak highly of his sermons.

As Fr Carlo used to speak English well and had a solid knowledge of theology, he was a very strong instrument in God’s hands for the conversion of Protestants in Malta. Service people often went to him – pilots, sailors and soldiers – to teach them Catechism before they are baptised. Other Parish Priests used to love refering them to him.

Moreover, the Parish Priest had a good pen and used to write passionate articles in the newspaper.

As Fr Edward Corrado told us, and as I remember myself, when we used to search for a solution of the case and it was the turn of the Parish Priest of Gżira to preside, his solution used to be so clear and simple that everyone used to be satisfied.

A devout man of the Eucharist and Our Lady

Some well-informed persons told us that Parish Priest Manché, although tired from work at the end of a day, often used to spend part of the night worshipping and meditating before the Holy Tabernacle in church.

Parish Priest Manché’s most favourite feasts were Corpus Christi, Sacred Heart of Jesus and Our Lady of Carmel, the patron of his parish. He was especially devoted to St John Baptist de la Salle, founder of the Frères, of whom he commissioned Guido Calì to make a painting for the church.

Duty and Sacrifice

You will remember me telling you that Fr Carlo used to enjoy smoking cigarettes. Later on he started smoking the pipe and some of his parishioners used to draw a mental picture of him as the Parish Priest, with the overcoat over his shoulders in winter and the pipe in his mouth, going out with the sacristan, with a priest or with the police, doing the rounds in his parish to stop as many abuses as possible. We were told that sometimes he received life threats from malicious people for continuing to perform his duties, but he was never afraid of these threats.

As we were told by a former sacristan of Gżira, Antonio Grima, who considerably assisted Parish Priest Manché with collections for the proper furnishing of the church, when the war broke out in 1939, as there were no shelters, the Parish Priest opened the doors to the belfries so that people could take shelter underneath. Together with Dr Colombo, he worked hard to have war shelters dug out as a matter of urgency. A Parish Priest and a doctor were always prepared to assist spiritually and physically whenever someone was injured in a bombing disaster.

A Man of Poverty

Parish Priest Manché lived a life of mortification, far from the luxuries and noises of the world. Apart from the deprivation of his family, which he suffered in order to help his colleague priests, he used to deprive himself of everything that was not necessary. He started with the parish house where he only occupied two rooms – a bedroom and the parish office, poorly furnished. And, remember, Fr Carlo did not come from a poor family, but from one that did not need anything. For this reason, the deprivation was more strongly felt. The only item of luxury (if you can call it that, these days) was the radio, because for him music was a hobby and recreation. He used to say that he used to rest mentally and physically when he went to eat with the Frères of Stella Maris College of Gżira, or when he would repair a clock.

He used to deprive himself of drink, sweets and desserts. On one occasion, his sister Mrs Mary Borg Manché told us, Fr Carlo was invited over to eat at their place and after dinner they offered him a piece of fruit. “To eat fruit,” Fr Carlo told them, “one must work for it. Our fruit is in the other world.”

All those who gave evidence told us that Parish Priest Manché was a most charitable and generous priest. What he had, was not his, because he soon gave it away to the poor and to those who asked for it, even though some used to make fun of him. Someone said that never did anyone go to him begging and left empty-handed. Often he helped women who were in danger of losing their reputation because of lack of money. We found out that he would even give away new clothes that he would have bought for himself or received from a member of his family, and keep the old clothes for himself.

Mons Karmenu Farrugia, ex-Parish Priest of St Gregory’s, told us that he had heard that Fr Carlo Manché wanted to apply for the professorship of Philosophy in our University (and it suited him and he was capable for it) not for the honour, but to earn more money, so he would have more to distribute to the poor. But he found that the two responsibilities were incompatible, and he ended up not applying. “Only God knows how much charity he did with the poor,” some witnesses told us.

The generosity of Parish Priest Manché was something extraordinary, not to say exaggerated. Visit him, show him that you liked something that he had and he would ask you: “Do you like it? Do you want it? Have it.” His brother, Prof. Joseph Manché told me that once he saw his precious old copy of the Bible. He picked it up and showed his appreciation of it. His Parish Priest brother told him: “Do you like it? Have it.” “Oh no, I would never take such a Bible as this from you!” “If you don’t take it, someone else will.” “If someone else will, then I will take it.” And the Professor took it and he still treasures it as a keepsake.

Fr Emmanuel Zammit told us that once Fr Carlo requested permission from Archbishop Gonzi in writing to become a Carmelite monk. The Archbishop replied: “I would like you to withdraw your request, because your mission as parish priest of Gżira has not yet been completed.”

He loved the Religious and the Associations

The Parish Priest was happy about the help that he received in the parish not just from the priests, but also from the religious and the laity.

During his time, the Frères inaugurated a large and beautiful college under the old name of Stella Maris College, where the Parish Priest often went to preach or officiate at a function. He also introduced the Augustinian Sisters to the parish. They opened a convent, church and school. He was their confessor, consultant and benefactor.

Also during his time the Catholic Action and the Legion of Mary were founded.

To attract people he turned the courtyard of the parish house into a little theatre and set up a band managed by the Catholic Action. In fact, the president of this society, who was my cousin Karmenu Grixti, was the president of the Mount Carmel Band.

The Death of Saints is precious

It is written in the Scripture: “Precious before the Lord is the death of his Saints”. For that reason, the death of Parish Priest Carlo Manché, who lived a holy life, had to be precious before God.

When he died he was only 45 years old. Some time before he died, he suffered an attack of thrombosis. The Frères offered to make arrangements for him to have a rest in their Mother House in Rome, Italy. It is said that the Archbishop wanted to appoint him Monsignor in order to alleviate the weight of parish responsibilities. However, like a brave soldier, he wanted to die with the sword in his hand on the battlefield.

Three days before he died, according to his brother the Professor, Fr Carlo visited him, and as a doctor he examined him and told him: “You better go home and go straight to bed.” Home he did go, but he did not go to bed because he wanted to continue working in his parish. His health continued to give clear indications that death was not far away.

On 18 November 1950 – on a Saturday – the doctor requested that Fr Carlo be given the last sacraments. Members of his family were duly called. Fr Luigi Cutajar, a Carmelitan, went over to comfort him. Fr Carlo, with a great devotion to Our Lady, kissed the scapular of Our Lady. Fr Edward Corrado administered the Last Rites to Fr Carlo. That same night, Fr Carlo relinquished his soul in God’s hands. The following day the Great Mission was scheduled to start in his parish. Do you think that the Parish Priest, as one witness observed, offered himself to God as a victim for the conversion of sinners in the parish during that Mission?

The Funeral

The funeral took place the following day, on Sunday. They carried him throughout the streets of Gżira dressed in liturgical clothing in an open coffin. Four Parish Priest colleagues were pall-bearers and his family walked behind the coffin leading a long procession, which included a representative of the Archbishop, the Minister of Emigration, the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, the Leader of the Constitutional Party, a large group of diocesan and religious priests, the Catholic associations and the university students.

The flags in Gżira were flying at half-mast, the house doors were shut, shops displayed a black sash showing respect, and men wore black ties. A huge sense of loss filled the air and people were crying everywhere.

He had nothing but took much with him

What did Parish Priest Manché leave behind? A metal bed with wooden slats, a grass mattress, two feather pillows, a chair, a table, a small box full of stuff, a shelf with some books, a clock and a torn pair of shoes.

Fr Edward Corrado told us that he did not know whether Fr Carlo left any money at all. He did know that he never saw him with any money except for that, which belonged to the church. Professor Manché told me: “Far from leaving behind any money, we had to pay back a debt of £400 which he had borrowed from the Curia for the benefit of the parish and which he had still not paid.” The Manché family were generous enough to contribute to the amount and paid off the debt. Instead of inheriting they had to pay. But God will pay them back a hundredfold.

Parish Priest Carlo Manché left nothing behind because all he had he shared with the poor and spent it for the benefit of the parish. But with him he took thousands and thousands of good and holy deeds that he did during his life. And God certainly gave him the reward for them in Heaven.

The Society of the Priests “Christus Rex” published this biography in Maltese to honour Parish Priest Carlo Manché on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of his death in 1975. Christus Rex thanks especially Mons Prof Arturo Bonnici who accepted the task to write this biography of Parish Priest Manché.

The Society also thanks all those who provided information about Parish Priest Manché, among them Chev. Joseph Borg, Mr Hector Borg, Mrs Mary Borg Manché, Fr Anton Calleja, Mr Gianni Cauchi, Fr Edward Corrado, Fr Luigi Cutajar OC, Mr Antonio Farrugia, Mons Carmelo Farrugia, Mr Joseph Formosa Holt, Mr Antonio Grima, Mr Mabbli Mamo, Prof Joseph Manché, Mr George Muscat, Bro. Robert Sammut FSC, Sr Eustachia Schembri, Augustinian Order, Bro. Emmanuel Sciberras SFC, Mr Henry Scicluna, Mr Carmelo Tabone, Fr Manwel Zammit.

Translated from the Maltese language by Edwin Borg-Manché